It’s A Long, Long Road to Freedom

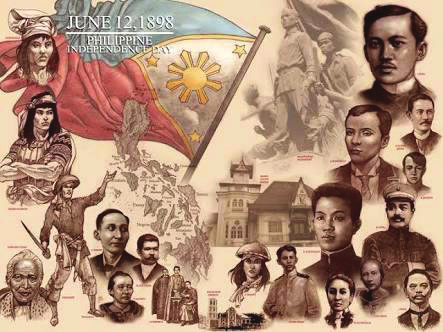

Every year, sometime around this period, amongst the reflective, there tends to rise an argument about how the Twelfth of June cannot historically be recognised as the Day of Philippine Independence. It was on that vibrant day when the Declaration of Philippine Independence was read, and General Emilio Aguinaldo waved the present- day Philippine flag from the balcony of his house in Cavite. In truth, the Declaration made on that day, roundly applauded by the crowd that had assembled below, was more of an aspiration that it was a fact. It would take another 48 years, on the Fourth of July 1946, before The Philippines would be win its emancipation from colonial occupation and be acknowledged by the international community as having gained its right to self-rule. And even then, as it is now, it is doubted if, indeed, the Filipino nation has unshackled itself from the dictates of foreign political and economic domination. In this, even the learned Pilosopo Tasio of Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere would have been eternally confounded.

Going through the chronology of events in the history of the nation, and the significant figures that played a role, might be somewhat relevant,andrevealingofintentionsthat preparefuturepaths.

From April 1565 to 1899, The Philippines was Spanish territory, administered from Mexico through the Viceroyalty of the New Spain.

Although Spanish rule generally brought progress to the islands, abuse of power by members of ruling class in terms of human rights, oppressive labour, exorbitant tax impositions, and social repression had been cause for gravest concern. Across the country, at different times, the Spanish rulers have had to parry numerous sporadic revolts against their governance across the country. The educated class of Filipinos had tried to appeal and negotiate for administrative reforms, to no avail.

In February 1872, three members of the clergy, Padres Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora were executed by guillotine over trumped up accusations of involvement in a workers’ mutiny in a naval shipyard in Cavite, over issues of pay reduction and increased taxation.

In 1887, the book Noli Me Tangere was published, a seething commentary on the abuses of Spanish governance in the Philippines, followed by El Filibusterismo in 1891, a sequel to Noli, wherein an actual uprising against the government was part of the narrative.

In 1892, Jose Rizal founded the organisation La Liga Filipina, which called for political reforms in Spain’s colonial government. Andres Bonifacio was a founding member. In July of that year, on the day Rizal was arrested and deported to Dapitan in southern Philippines, Bonifacio officially declared the founding of the secret organisation Katipunan, which sought independence from Spain through armed revolt. Bonifacio would soon abandon support for La Liga Filipina, as he no longer believed in mere reforms.

By 1896, the membership of KKK had increased to 30,000, owing to the publication of an official organ, Kalayaan, a collaboration between Bonifacio and Emilio Jacinto who wrote the KKK’s charter called Kartilya. Members included Emilio Jacinto, Apolinario Mabini, and Emilio Aguinaldo.

In August 1896, Katipunan having attracted attention, was exposed to authorities, which left Bonifacio with no choice but to launch the revolution earlier than planned. With himself as supreme commander, he began an open charge with what is referred to as the Cry of Balintawak or Pugadlawin. Rizal was on his way to Cuba on a medical mission for the government in exchange for his release. When the revolution broke out, however, he was arrested.

On December 30, 1896, Rizal was executed, accused of leading the social uprising. The Filipino rebellion continued to be fought in 3 fronts, with Emilio Aguinaldo commanding the Cavite front with some success, as the Spanish forces focused their attention against Bonifacio in Manila and northeastern parts. A leadership conflict developed between Aguinaldo and Bonifacio.

Political feuding amongst the rebel groups came to a head, after Aguinaldo established himself as president of the Republic at the Tejeros Convention in Cavite. When Bonifacio refused to abide by the convention, Aguinaldo had him arrested, tried in a kangaroo court, and executed in March 1897. Andres Bonifacio suffered death in the hands of comrades, along with two brothers and his wife.

The campaign against the Spanish government ended in December 1897. Spanish forces caught up with Aguinaldo’s troops who made a retreat in Bulacan and set up the Republic of Biak-na- Bato. A ceasefire was called and a pact signed by the Spanish colonial Governor- General Fernando Primo de Rivera and the revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo on December 15, 1897, which called for Aguinaldo and his militia to surrender. A monetary indemnity by the Spanish government was given to Aguinaldo and his men, in return for which they agreed to go into exile in Hong Kong.

In April 1898, while the Philippines was still under the Spanish East Indies regime, Spain and the United States declared war on each other.

The first confrontation the Spanish– American War took place in the Philippines on May 1,1898 in Manila Bay. In a matter of hours, Commodore George Dewey’s squadron had defeated the Spanish squadron. The McKinley administration then made the decision to capture Manila from the Spanish.

In May 1898, Aguinaldo was transported back to the Philippines in a US vessel. After a brief meeting with Dewey, Aguinaldo resumed revolutionary activities against the Spanish. On May 24, Aguinaldo issued a proclamation in which he assumed command of all Philippine forces and announced his intention to establish a dictatorial government headed by himself, saying that he would resign in favor of a duly elected president.

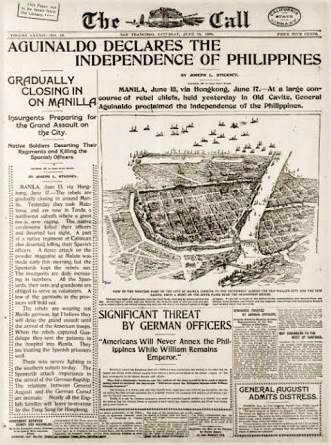

On 12 June 1898, Aguinaldo proclaimed the independence of the Philippines at his house in Cavite El Viejo. On June 23, Aguinaldo issued a decree, this time establishing a revolutionary government and naming himself as President.

On August 12, 1898, a peace protocol was signed in Washington between the U.S. and Spain, stating in part that “The United States will occupy and hold the City, Bay, and Harbor of Manila, pending the conclusion of a treaty of peace, which shall determine the control, disposition, and government of the Philippines.” After conclusion of this agreement, U.S. President McKinley proclaimed a suspension of hostilities with Spain.

The U.S. established a military government in the Philippines, with General Merritt acting as military governor. It marked the end of Filipino-American collaboration, and the beginning of the Philippine American hostilities.

Aguinaldo’s Revolutionary Government held elections between June and September of 1898, with Emilio Aguinaldo as President of what is known as the Malolos Congress. By November 1898, the Malolos Constitution was adopted, creating the First Philippine Republic.

Meanwhile in October 1898, the Treaty of Paris convened, with the McKinley government demanding from Spain the cessation of the entire Philippine archipelago. Furious at first, the Spaniards capitulated, after an offer of $20,000,000 was offered by the US “for Spanish improvements” to the islands.

On December 10, 1898, Treaty of Paris was signed, formally ending the Spanish– American War. In Article III, Spain ceded the Philippine archipelago to the United States.

In February 2, 1899, the first shot was fired in the Battle of Manila, combat ensuing between the Filipinos and the Americans.. The Filipino troops were routed. By March 31st, Malolos had been captured by the Americans, as Aguinaldo escaped.

Two months prior, in January 20, 1899, the Mckinley government had created the 5-member- Schurman Commission (First Philippine Commission), 3 members arriving in Manila in April, amidst the raging conflict between the US and revolutionary Filipino forces. The commission issued a proclamation that the US “… is anxious to establish in the Philippine Islands an enlightened system of government under which the Philippine people may enjoy the largest measure of home rule and the amplest liberty.”

After meetings with revolutionary representatives in April 1899, the commission requested authorization from McKinley to make the Filipinos an offer for a government consisting of “a Governor- General appointed by the President; cabinet appointed by the Governor- General; [and] a general advisory council elected by the people.” The Revolutionary Congress voted unanimously to cease fighting and accept peace. But on May 8, the revolutionary cabinet headed by Apolinario Mabini was replaced by a new “peace” cabinet headed by Pedro Paterno.

At this point, General Antonio Luna arrested Paterno and most of his cabinet, returning Mabini and his cabinet to power. Seeing all this, the commission concluded that “… The Filipinos are wholly unprepared for independence … there being no Philippine nation, but only a collection of different peoples.”

In November 1899, the Schurman Commission issued a preliminary report containing the following statement: “Should our power by any fatality be withdrawn, the commission believe that the government of the Philippines would speedily lapse into anarchy, which would excuse, if it did not necessitate, the intervention of other powers and the eventual division of the islands among them. Only through American occupation, therefore, is the idea of a free, self-governing, and united Philippine commonwealth at all conceivable. And the indispensable need from the Filipino point of view of maintaining American sovereignty over the archipelago is recognized by all intelligent Filipinos and even by those insurgents who desire an American protectorate. The latter, it is true, would take the revenues and leave us the responsibilities. Nevertheless, they recognize the indubitable fact that the Filipinos cannot stand alone. Thus the welfare of the Filipinos coincides with the dictates of national honour in forbidding our abandonment of the archipelago. We cannot from any point of view escape the responsibilities of government which our sovereignty entails; and the commission is strongly persuaded that the performance of our national duty will prove the greatest blessing to the peoples of the Philippine Islands.”

Specific recommendations included the establishment of civilian government as rapidly as possible (the American chief executive in the islands at that time was the military governor), including establishment of a bicameral legislature, autonomous governments on the provincial and municipal levels, and a system of free public elementary schools.

In March 16, 1900, the Second Philippine Commission was appointed, headed by William Howard Taft, and granted legislative as well as limited executive powers. The Taft Commission began to exercise legislative functions. Between September 1900 and August 1902, it issued 499 laws, established a judicial system, including a supreme court, drew up a legal code, and organized a civil service.

In March 1901, Aguinaldo was captured by American forces and swore allegiance to the United States, then issued a declaration abandoning any further resistance to American rule.

In July 1901, the US civil government in the Philippines was inaugurated with William H. Taft as the Civil Governor.

The Philippine Organic Act of July 1902 established the Philippine Commission and stipulated that the bicameral Philippine Legislature would be established. The act also provided for extending the United States Bill of Rights to the Philippines.

Every year from 1907 the Philippine Assembly and later the Philippine Legislature passed resolutions expressing the Filipino desire for independence.

Philippine nationalists enthusiastically endorsed the Jones Law, officially the Philippine Autonomy Act, which served as the new organic act (or constitution) for the Philippines. Its preamble stated that the eventual independence of the Philippines would be subject to the establishment of a stable government.

During the First World War, the Filipinos suspended their independence campaign and supported the United States against Germany. The campaign was resumed after the war.

On March 17, 1919, the Philippine Legislature passed a “Declaration of Purposes”, which stated the inflexible desire of the Filipino people to be free and sovereign.

In January1933, the Hare–Hawes–Cutting Act promised Philippine independence after 10 years, but reserved several military and naval bases for the United States, and imposed tariffs and quotas on Philippine exports. Manuel L. Quezon urged the Philippine Senate to reject the bill, to secure a better independence act. The Tydings- McDuffie Act was the result, ratified by the Philippine Senate, and provided for the granting of Philippine independence by 1946.

On December 7, 1941, a few hours after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese launched air raids in several cities and US military installations in the Philippines. On December 8, and on December 10, the first Japanese troops landed in Northern Luzon. The Philippines would be under Japanese occupation for the next 3 years. Over a million Filipinos, including regular and constable soldiers, guerrillas and non-combatant civilians) would be killed in the war, and many towns and cities, including Manila, would be left in ruins.

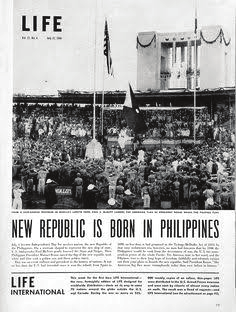

Philippine independence came on July 4, 1946, with the signing of the Treaty of Manila between the governments of the United States and the Philippines. The treaty provided for the recognition of the independence of the Republic of the Philippines and the relinquishment of American sovereignty over the Philippine Islands.

From 1946 to 1961, Independence Day was observed on the Fourth of July.

In May 1962, President Diosdado Macapagal issued Presidential Proclamation No. 28, proclaiming Tuesday, June 12 that year as a special public holiday throughout the Philippines. In 1964, Republic Act No. 4166 changed the date of Independence Day to the Twelfth of June, renaming the Fourth of July as Philippine Republic Day. –-Text extracts from Wikipedia articlesourcesonPhilippineIndependence, The Philippine Revolution, and History of The Philippines1898-1946.

Today, the Philippines is a sovereign country… Haring Bayan, as Andres Bonifacio hadaspiredto.Butastowhetherwehold our destiny in our own hands, and whether we are now “one nation or just a collection of different peoples”… those are the hard questions that we continue to grapple with. One hundred twenty years after both Bonifacio and Jose Rizal were martyred, we are still struggling.

It’s a long road to freedom,” the folk song goes…”The winding steep and high.” However, indeed, we have a choice. “[For] when you walk in love with the wind on your wing, And cover the earth with the songs you sing…The miles [can] fly by…” The Pinoy Strayan